01/21/26 12:01 pm

Earlier this week, I went to Philadelphia to watch a live Taskmaster comedy show. After the show, I went backstage for a meet-and-greet with Alex Horne and Greg Davies, the cohosts of the show. It was awesome.

I got the opportunity to do the meet-and-greet simply because I asked.

(If you’re not familiar with Taskmaster, it’s a hit British comedy panel series that’s launched numerous international spinoffs, and it’s one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen. I legitimately love it.)

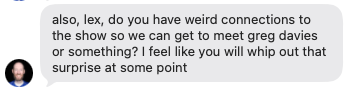

My friend Scott invited me to join him at the show. We found out that our friend Matt was going, too. And Matt sent a group text:

I hadn’t thought about leveraging any connections at this show. I hadn’t even bought tickets! But Matt’s text jogged my memory: I’d worked with a talent agent who was also an executive producer for Taskmaster. I could ask him about the chance for a meet-and-greet.

Now, let me be clear: This agent owes me nothing. It’s been years since I left the corporate podcasting world, and I can’t offer any of his talent roster a deal for oodles of money. But I’d done well by the agent in years past, and I simply concluded: It couldn’t hurt to ask.

So I asked. And 24 hours later, after he connected me to a tour manager, who connected me to another person on the tour, who connected me with a third person involved with the tour logistics, I was on a WhatsApp chain handling the details of how we’d get backstage after the show to meet Greg and Alex.

All because: I simply asked. The worst-case scenario was that the agent would say “No, sorry.” In which case, I’d still get to see the show, I’d tell Scott and Matt that I’d tried and failed, and we’d all move on with our lives. I had nothing to lose.

But in fact the agent did help me out, and I spent about a half hour in conversation with Alex after the show. It was awesome.

Halfway through the show, in fact, Alex and Greg introduced special guest comedian Chris Gethard. And I know Chris! I worked with him on his podcast for years. So I texted him right then, from the audience. (Chris is a professional. He didn’t see my message until after the show.)

Chris hung out backstage too, and I genuinely don’t know if a comedian has ever been nicer to me. When Alex asked Chris how we knew each other, Chris talked about me in glowing terms, giving me (unearned!) credit for helping with his podcast and career. Even as I protested that his description of me was frankly too rosy, it didn’t matter: Alex now saw me as someone worth talking to, and that was all thanks to Chris.

Almost entirely coincidentally, I am now trying to help Alex and Taskmaster reach a certain comedian he mentioned as a dream guest, and with whom I happen to have a slight connection. But there was no way Alex or his agent knew that comedian would come up in conversation during an onstage Q&A, or that I would have a loose connection to that person.

My point in sharing this story is that it’s okay to ask for the thing sometimes. Most decent humans like helping other humans out. The fact that the agent knew he likely could make a meet-and-greet happen probably made him feel good about saying yes. And my friends and I were thrilled to meet everyone.

I tell my kids all the time that one of the most important lessons I want to impart upon them is the idea of advocating for themselves. If the biggest risk in Just Asking for the thing is that you might get a “no” in response, go for it. Because you also might get a yes.